Will boards be held accountable for political risk?

Geopolitical events have exposed big corporations to unanticipated problems and financial losses, underscoring the limitations of existing risk mitigation strategies

Geopolitical events have exposed big corporations to unanticipated problems and financial losses, underscoring the limitations of existing risk mitigation strategies

Simon Coote, Deputy Director of Research at global analysis and advisory firm, Oxford Analytica, looks at how geopolitcal risk is affecting big companies

Geopolitical events, including the Arab Spring, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, have exposed multinationals to unanticipated challenges that have caused financial losses – and, in turn, they have underscored the limitations of existing risk mitigation strategies.

A new report, titled How are leading companies managing today’s geopolitical risks? from Willis Towers Watson and Oxford Analytica, suggests that executives across a cross section of industries, including some of the world’s leading firms, think political risk is set to become an active fiduciary responsibility that investors will hold the board to account for.

Political risk has always existed but, particularly in Europe and the US, political change has historically tended to be predictable and incremental. The developed world had “legal reliability”, as one energy industry executive put it.

Such certainties have evaporated, producing a new and difficult-to-classify geopolitical threat. An executive in the automotive industry noted that “opinions, regulations, and initiatives are not being built from the same base”. In the near term, many executives expressed concerns around trade policy and protectionism, and particularly the future of NAFTA.

Since the financial crisis, low and negative growth in Europe and North America has created an environment of uncertainty and a focus on inequality. In response, one executive argued, it is unsurprising that governments are using regulation as a policy tool to address differences between the haves and have-nots.

Perhaps as a response, several of our executives mentioned localisation strategies as being central to their political risk mitigation toolkit. “In many countries where we do business, people think we are a local company”, as one food and beverages executive noted. A mining executive said: “in-country holding companies should be a means to bring in independent locals and establishing good relations”. Several executives mentioned the crucial importance of having in-country government relations teams in each market where the company operates.

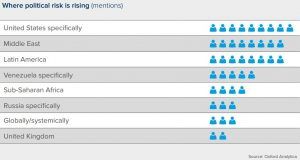

In a dramatic sign of the changing times, the United States was cited as the market of most concern in terms of rising political risk. The unpredictability of both US international and domestic policy has led to tangible top and bottom line implications for many multi-national companies. Several executives, for example, highlighted exchange rate losses in Mexico due to the US administration’s rhetoric, while all healthcare executives cited the impact efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act is having on their businesses.

One executive took the view that the United States “is withdrawing from the world stage”, which is creating challenges for corporate planning and supply chains. For instance, if one’s Asia headquarters is centred in Singapore, “is that still a wise decision if the US approach to the region may be changing?”

More broadly, as an energy sector executive noted, it has been “a largely unspoken but widely held assumption” that the main corporate risk exposure in developed markets is economic risk, and in developing markets is political risk. The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis at first appeared to confirm this assumption. “But the subsequent response to austerity measures adopted after 2008 in developed economies has led to a situation where risk there is very much political now,” he noted.

Of course, the leading companies we interviewed were not taking a passive response to the changing risk environment. Many had already made major changes to their political risk management approaches, and created new corporate capabilities. In several cases, these changes involved new processes that enabled corporations to marshal their organisational resources effectively, bringing intelligence from one part of the company to another, or bringing risk management staff together with government relations or business development.

Other executives noted changes in reporting and responsibility. For instance, an executive in the building materials sector noted that the enterprise risk management function was no longer simply a source of intelligence and advice; it played an active role in devising solutions and reported to the board of directors. Another executive in the food and beverages sector noted that the executive board had been made directly responsible for political risk – an increasingly popular approach.

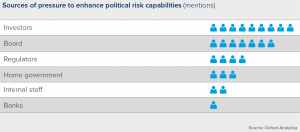

Most of the executives noted rising pressure from external stakeholders regarding political risk management. About half specifically mentioned institutional investors; roughly four in ten mentioned the board.

As a result, the CEO and CFO increasingly appreciate that political risk is one of the factors that can be crucial in determining the success of country and global operations. Investors want predictability and, therefore, it is likely that CEOs will increasingly be measured on their ability to manage political risk. “Investors see us as a stable stock and expect us to manage this kind of risk as a matter of course”, as one executive put it.

Most executives mentioned a growing pressure, both internal and external, for quantification. “One issue is that the technical people who tend to be in management at this organization like numbers” noted one energy sector executive. “They want to quantify political risk”. An executive from the mining sector said: “Questions about how changing risks affect calculations around the value of the company are being asked by investors, and the company needs to show quantitative answers”.

The nature of political risk is changing, with the apparent end of the US-dominated globalisation system and a growing regulatory reaction to inequality. As a result, the incorporation of political risk into corporate planning cycles is becoming more operationally focused and shorter term.

The incorporation of political risk into operational decision-making will require an increasing mix between qualitative and quantitative analysis in order to “inform, warn and persuade” different internal and external stakeholders.

Leading companies have suffered political risk losses, and agree that geopolitical risk levels and volatility have risen. For external stakeholders, a limited understanding of these losses and potential exposure to future losses is prompting a tide change: political risk is set to become an active fiduciary responsibility, for which investors will increasingly hold senior management and the board to account.

Growing institutional pressure is likely to mean that companies will, over time, be compelled to benchmark political risk exposure and capabilities against their peers, which will present many organisational challenges. While some corporations are already responding proactively, building new capabilities and adopting new mitigation techniques, will depend on:

If done correctly, this will strengthen the political risk function’s ability to, for instance, push a negative non-consensus view against a Sales department focused on the topline, or a country that wants investment for growth. At the moment, the disparity and informality of frameworks limit the risk function’s influence to stakeholders that “speak the same language”.